By Linda Lanoue, Certified Texas Master Naturalist

Way-Back Machine: May 3, 2012

Twice a year, Dr. Larry Niles from Conserve Wildlife New Jersey, and Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program (CBBEP) put together a team to gather information about Red Knots on Padre Island National Seashore. On October 4th, the team was headed up by Dr. Niles, along with David Newstead and Owen Fitzsimmons of CBBEP. They were also people from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and a graduate student from the University of Texas. Clark Williams, Fred Lanoue, and I represented Mid-Coast Texas Master Naturalists. Chapter member Brigid Berger and Chapter Advisor Brent Ortego participated earlier in the week.

For non-birders, a Red Knot is a small shorebird. It breeds in the Arctic, and can winter as far south as Tierra del Fuego, South America. That’s a long journey for a bird that weighs less than 5 ounces! Not much is known about the birds and their habits, which is why finding out more about them is important. Their numbers have sharply declined in recent years, and Red Knots are being considered for federal listing as an endangered species.

I wasn’t sure what to expect. The information given was that we should be prepared for a long day in bouncy 4-wheel drive vehicles, no bathrooms, hot sun, biting insects, and lots of sand on everything. That sounded a lot like Matagorda Island Turtle Patrol to me. Although I was pretty sure we wouldn’t be finding turtle nests, I knew I’d feel right at home.

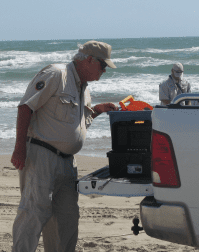

The trapping was done using a cannon net, so the first thing we did was prepare the charges. Very small plastic bags were filled with black powder, and an electric match was embedded in the powder. The bags were sealed, leaving the wire for the match sticking out. One charge would be loaded in each side of the cannon connected to a longer single wire, so that the charges could be set off simultaneously from a distance. Then the net was carefully loaded into the cannon.

A lot of the day was spent squeezed into 4-wheel drive pickups. We drove slowly down the beach, looking for Red Knots. The first ones spotted had recent tags, so we didn’t bother them. They are remarkably tolerant of vehicle traffic, and didn’t get nervous unless we stopped the truck too near them.

When we found a group of unbanded birds, it was time to get down to business. First, we watched from a distance to try to determine which direction they were going. Then the cannon was set up ahead of them, in hopes they would walk into range as they fed. If they decided to go in the wrong direction, someone would walk along slowly & try to move them in the right direction. With an incoming tide, sometimes the cannon got flooded before the birds were within range. Then it had to be unloaded, thoroughly dried, and reloaded.

The safety and well-being of the birds was always a prime concern. As they got into range, one of the leaders was always close to the birds & in radio contact with the person setting off the charge. If any birds were in a position where they might be hit with the edge of the net, it wasn’t fired until they were safe. With the exception of the leaders, we were all in the trucks, watching and waiting.

As soon as the net was fired, we rushed into action as quickly as we could. Some ran to the net to start untangling the birds, while others hurriedly set up the canopy to provide shade for the birds while they were being processed. Everyone was assigned a job. My job was to record data, Fred weighed, and Clark helped take blood samples. Others banded; measured wings, heads, & bills; decided the age; and fitted some birds with geolocators. If any birds are recaptured, the geolocators can be removed for data retrieval. In order to release the birds as quickly as possible, 3 or 4 birds were processed at once. After all were released, the canopy was taken down, equipment was packed up, and we were back in the trucks to try again.

In the 5 days, only about 50 birds were captured—only about half the number anticipated. Unfortunately, we didn’t find a single bird with a geolocator from previous years. Although these were disappointments, it was a fascinating, wonderful experience, and I’m looking forward to trying again in April. I love being a Mid-Coast Texas Master Naturalist!

As soon as the net was fired, we rushed into action as quickly as we could. Some ran to the net to start untangling the birds, while others hurriedly set up the canopy to provide shade for the birds while they were being processed. Everyone was assigned a job. My job was to record data, Fred weighed, and Clark helped take blood samples. Others banded; measured wings, heads, & bills; decided the age; and fitted some birds with geolocators. If any birds are recaptured, the geolocators can be removed for data retrieval. In order to release the birds as quickly as possible, 3 or 4 birds were processed at once. After all were released, the canopy was taken down, equipment was packed up, and we were back in the trucks to try again.

In the 5 days, only about 50 birds were captured—only about half the number anticipated. Unfortunately, we didn’t find a single bird with a geolocator from previous years. Although these were disappointments, it was a fascinating, wonderful experience, and I’m looking forward to trying again in April. I love being a Mid-Coast Texas Master Naturalist!